2024-2 Social Ontology

Khalidi, Muhammad Ali (2015). Three Kinds of Social Kinds. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 90 (1):96-112.

1. Social Kinds and Human Kinds

Social kinds, or human kinds, are frequently said to be different from natural kinds for various reasons.

① they are ontologically subjective since they depend on human mental attitudes for their very existence (Searle 1995).

② they are different from natural kinds because they are interactive and can change in response to our attitudes towards them (Hacking 1995; 1999)

③ social kinds are fundamentally evaluative or normative in nature (Griffiths 2004)

In this paper, I will be examining the first claim about social kinds, which holds that they are ontologically subjective because they depend on beliefs or other propositional attitudes. Even though it appears as though some social kinds have the features that Searle says they do, I will argue that others do not. Moreover, even those that do conform to Searle’s picture of social kinds are not ineligible to be natural kinds for the reasons that he cites, but may not be natural kinds for other reasons, which I shall try to explain.

Before investigating the nature of social kinds, it may be worth getting clear on the extension of the expression. In particular, is there a difference between social kinds and human kinds? There may be human kinds that are not social (e.g. sickle cell anemia) or social kinds that are not human (e.g. dominant male, as applied to macaque monkeys; cf. Ereshefsky 2004). But the overlap between the two classes is sufficiently great and the commonalities between them are extensive enough as to warrant lumping them together. In case the exceptions on both sides appear to have special features that set them apart, the cases that will particularly interest me in what follows are kinds that can be considered instances of both. I will be focusing on those kinds that are both social and human and will omit from consideration non-social human kinds and non-human social kinds.

Social Kinds (SK) are not the same as Natural Kinds - trees, mollecules

2. Searle on Social Kinds

Searle: how can there be “things that exist only because we believe them to exist” (e.g. money, property, governments, and marriages), yet many facts about these things are objective facts?

ontological and epistemic subjectivity:

| Names | ontological subjectivity | epistemic subjectivity |

| Domains | applies to entities and types of entities | applies primarily to facts and judgments |

| Subjective | subjective entities (tokens or types) are ones whose mode of existence depends on being felt by subjects (though he might have added, thought or otherwise mentally apprehended) | a judgment is epistemically subjective when its truth or falsity depends on certain mental attitudes or feelings |

| Objective | objective entities do not exhibit such mental dependence | it is epistemically objective when it does not exhibit such dependence |

The Resoultion of the Puzzle: although social kinds (like money, marriage, private property, and elections) are ontologically subjective, judgments about them can be epistemically objective.

Thus, the kind money is ontologically subjective, since its existence depends on our mental attitudes, but the judgment that this coin is an instance of money or that is a ten-dollar bill is epistemically objective, since the truth of these judgments is independent of our attitudes.

Some social kinds have the character that Searle identifies, but other social kinds do not conform to his analysis. This point has been argued convincingly by Thomasson (2003a; 2003b), who criticizes Searle for failing to recognize that many social kinds do not depend for their existence on people’s having thoughts about those kinds themselves. As she points out, this may hold true of the kind money, but not of the kind recession (cf. inflation, racism, poverty)

Thomasson (2003a, 276; original emphasis) writes that “a given economic state can be a recession, even if no one thinks it is, and even if no one regards anything as a recession or any con ditions as sufficient for counting as a recession.” Similarly, she argues that “something or someone can be racist without anyone regarding anything as racist…” (2003a, 276). It is plausible that there was racism before that kind was identified and before anyone had any propositional attitudes involving the category racism itself.

In more recent work, Searle (2010, 116-117) acknowledges the existence of such kinds as recession, which are not dependent on our having attitudes towards them. But he maintains that these social kinds are “consequences” or “systematic fallouts” of the other kinds of social kinds, which do depend for their existence on our having attitudes towards them. Though he does not spell out precisely what he means by “consequences” or “systematic fallouts” (for instance, whether they are causal or conceptual consequences), or justify the claim in detail, it is sufficient for our purposes that Searle has come to acknowledge that there are some kinds of social kinds that do not depend for their existence on our having attitudes towards them.

This discussion suggests that there are three kinds of social kinds.

| ① | ② | ③ |

| social kinds whose nature is such that human beings need not have any propositional attitudes towards them for them to exist (사람들이 그렇다고 믿지 않는다고 해도 존재함) | those whose existence is at least partly dependent on specific attitudes that human beings have towards them, though these attitudes need not be in place towards each of their particular instances for them to be instances of those kinds (타입 차원에서는 사람들이 그렇다고 믿어야 존재하지만, 토큰 차원에서는 사람들의 믿음과 무관하게 존재함. 사람들의 믿음은 충분조건도 필요조건도 아님 ex) 생산된 후 한번도 사용되지 않은 1달러 돈///위조화폐) | those whose existence and that of their instances are both dependent on attitudes that human beings have towards them (타입차원에서 사람들이 그렇다고 믿어야 존재할 뿐만 아니라 토큰 차원에서도 사람들이 그렇다고 믿어야 존재함) |

| recession, racism | Money, War | permanent resident, prime minister |

① The existence of these kinds clearly depends on the existence of human beings and depends on those humans having certain propositional attitudes. There can only be racism in a society if some members of that society are prejudiced against others or harbor attitudes of superiority or contempt towards them insofar as they are members of a different group. But members of that society need not have any propositional attitudes that involve the category racism itself. They may never have consciously formu lated such a category or concept; indeed the racists may be in denial that they have such attitudes and the victims of racism may never have articulated the concept. Nevertheless, certain human propositional attitudes must clearly be in place for racism to exist.

② In these cases, at least some members of society need to have propositional attitudes involving these categories themselves. For money to exist, we need to have a practice and attitudes that make mention of the category money. But, as Searle says, there can be tokens of that type about which no one has any propositional attitudes, as in the ten-dollar bill that falls through the cracks.

Similarly, Searle may be right that for war to exist at all, there needs to be something like declarations of war; the practice of war depends on attitudes involving the concept war and related concepts. But even though Searle does not appear to agree, it may be that any individual act of war could be a war without it being considered such by the parties (or indeed anyone else). We may find that a border skirmish between Ruritania and Lusitania, which took place without a declaration of war on the part of either country, escalated and dragged on to the point that it could be considered a war, though no one considered it to be a war at the time.

The reason that this seems possible is that individual tokens of war are dependent not solely on the attitudes of members of society but also partly on certain causal properties. There may be no hard and fast conditions that a series of events needs to satisfy to be correctly considered a war, but there are certain criteria that historians, journalists, and others might employ. They might, for example, attend to the number of troops deployed, casualty figures, duration of hostilities, and other features to judge whether a conflict can indeed be deemed a war. Declarations of war are important to be sure, but they may be neither necessary nor indeed sufficient. If a war is declared but not a single shot is fired before a diplomatic solution is found, it may be perverse to consider that a war has indeed taken place.

Hence, the second kind of social kind may include kinds like war as well as kinds like money, since tokens of these kinds may be instantiated even though no one considers them to be such. Could there be war without beliefs involving the concept war, i.e. beliefs about the category itself? In other words, could war be in the first category (with recession and racism) rather than the second? It seems implausible. War is not just any large-scale outbreak of violence, but one that is orgaized, planned, and conducted according to certain rules (even if those rules are often more honored in the breach). Since those rules must be the outcome of human thought processes involving the category itself (or its close counterparts), it is not clear that the practice could get off the ground without some propositional attitudes involving the category itself. The same goes for money. Where there is currency in various denominations, there is surely a set of rules or conventions, whether explicit or implicit, and the introduction of such conventions requires having thoughts involving the category itself.

③ In this case, not only must some members of a society have attitudes towards the kind itself, each individual token of the kind can only be such if it has been considered to be such by some members of society. To illustrate—though I shall dispute that this is a good illustration—Searle (1995, 34) describes a cocktail party gone wild:

If, for example, we give a big cocktail party, and invite everyone in Paris, and if things get out of hand, and it turns out that the casualty rate is greater than the Battle of Austerlitz–all the same, it is not a war; it is just one amazing cocktail party; part of being a war is being thought to be a war.

In this case, Searle (1995, 34) claims that “the attitude that we take toward the phenomenon is partly constitutive of the phenomenon.” He does not say that all there is to being a cocktail party is being thought to be one, but he does regard it as a necessary condition on individual tokens of cocktail parties that they be thought to be such. I argued above that this is not the case for wars, and nor is it obviously the case for cocktail parties. It is not out of the question for a social gathering to be a cocktail party, though no one conceives of it as one (say, a political fundraiser at which no funds are raised). And it is certainly not obvious that Searle’s Parisian bash is indeed a cocktail party, though it is widely considered to be such. Even if the organizers and participants all continue to insist that it was just one big chaotic cocktail party, it would not be absurd for someone else (say, a bystander, judge, or sociologist) to conclude correctly that it was really a street fight or a brawl. Indeed, even if everyone were to agree that it was a cocktail party, it is surely not impossible for them all to be mistaken about its real nature. [Searle의 주장과 달리 칵테일 파티 사례는 세 번째 범주의 사회종에 속하지 않음]

At least for some social kinds of the conventional or institutional variety, even if all social actors agree that something counts as a token of social kind K that does not guarantee that it is indeed a member of kind K. Moreover, even if no one regards something as a token of social kind K, it may well be a member of kind K. Note that this is different from Thomasson’s point, which was discussed above. She argues correctly that when it comes to many social kinds (e.g. recession) we need have no attitudes towards them for them to be the kinds that they are. My point is that even for some of Searle’s institutional or conventional kinds, for which some attitudes need to be in place concerning the type, these attitudes may not need to be in place for each token of the type: we may all lack the attitude that it is a war when it really is a war, and we may all have the attitude that it is a cocktail party when it is not really a cocktail party. But the larger point is not that there are exceptions but that this shows that these kinds are not purely conventional, but at least partly causal in nature (as I will try to elaborate in the next section).

Are there any social kinds such that both their tokens and their types are dependent on human attitudes in the way that Searle suggests? Perhaps the best candidates are those that are more strictly institutional or conventional in character. This may hold for a social kind like permanent resident in a certain jurisdiction.

To have a category of permanent resident in a particular state requires there to be conditions set out by officials of that state, which entails their having attitudes involving that category itself.

+

Moreover, no individual could be a permanent resident of that state without certain officials having the requisite attitudes towards them (viz. that they satisfy the conditions).

=

In this case, at least some members of society need to have certain propositional attitudes involving the category for the existence of the type, and they must also have propositional attitudes involving the category that are directed towards an individual for the instantiation of a particular token of that type.

Searle’s thesis holds more nearly when it comes to social kinds of a purely conventional nature, that is kinds whose associated properties or conditions of membership are more strictly laid out in a set of rules or laws. When it comes to a social kind like permanent resident, in many jurisdictions, requirements are set out that specify what conditions one has to satisfy to be a permanent resident of that jurisdiction (e.g. that one not have a criminal record). Moreover, whether or not any particular individual satisfies these conditions is a matter to be decided by the beliefs and other attitudes of members of the relevant society. To be sure, it is not the attitudes of members of society at large that determine one’s status as a permanent resident, for this is usually determined by the attitudes of officials of the state, who are informed by the appropriate laws and statutes. Officials may make mistakes concerning the conditions that a person meets (e.g. they may think that she has a criminal record when she does not), but even when they do so, it is usually their beliefs or say-so that determine whether someone is a permanent resident or not. In such cases, it is the beliefs of officials—informed by an explicit convention or law—that determine whether someone is or is not a permanent resident.

Similar considerations apply to a social kind like prime minister. One cannot be the prime minister of a certain state unless there is such a political office governed by statutes specifying the qualifications of the holder of that office, the means of selecting the office holder, the duties and prerogatives of the office holder, and so on, all of which entail having attitudes involving the category itself. Even more clearly, there could not be such a thing as an individual prime minister unless she were selected in the specified manner and deemed as such by the relevant authorities, a process which involves having the appropriate attitudes towards her. It could be objected that Pericles was effective prime minister of Athens in the period before the Peloponnesian War, though there was no such office and no one explicitly considered him to be such. Plutarch said of him that he had “for forty years together maintained the first place among [Athenian] statesmen…,” and Xenophon called him the chief ruler of the state. But to describe him as prime minister is to speak figuratively and to attempt an analogy with later systems of government. I think it is safe to conclude that the social kind prime minister could not be manifested unless there were laws or conventions in place involving the kind itself, and no individual could be an instance of the kind prime minister unless she were considered to be an instance of that kind.

Generally, the most conventional of social kinds are such that certain explicit conventions need to be in place for the existence of the kind as a whole, and individuals must have the convention applied to them to qualify as instances of that kind. In both cases, this entails having attitudes towards the kind itself.

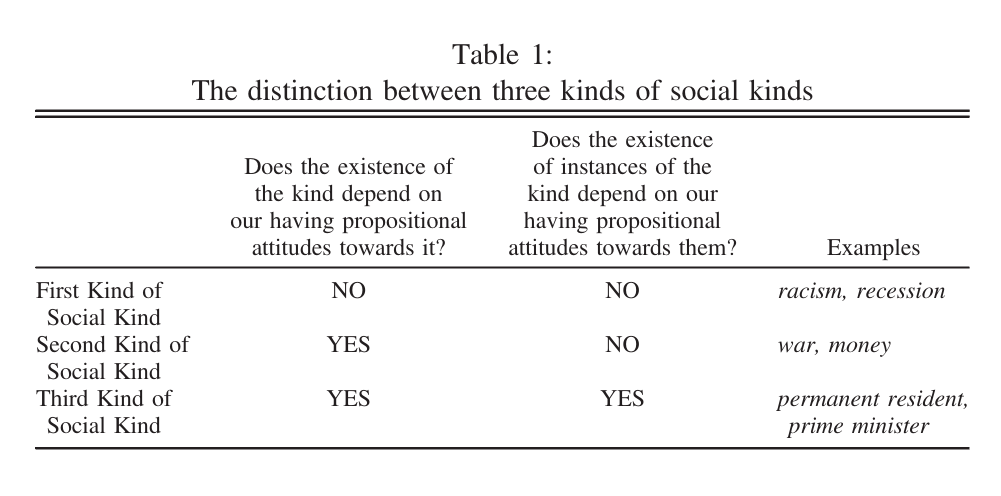

To sum up, we can ask two related questions about social kinds: (i) Does the existence of the kind depend upon our having certain propositional attitudes towards it? (ii) Does the existence of instances of the kind depend on our having propositional attitudes towards them, namely that they are instances of that kind?

The first category of social kinds receives a negative answer to both questions, while the second category receives an affirmative answer to the first question and a negative to the second, and the third category receives an affirmative answer to both questions. In addition to the fact that Searle initially ignored kinds belonging to the first category (e.g. racism, reces sion), he puts some kinds into the third category that belong more properly to the second category (e.g. war, money). Moreover, I would conjecture that the kinds that belong to the third category are those that are more purely institutional or conventional (e.g. permanent resident, prime minister). The distinction between the three kinds of social kinds can be summarized in tabular form (see Table 1).

3. Conventions and Causes

In the previous section, I delineated three kinds of social kinds.

The first kind of social kind is mind-dependent in the sense that at least some human mental states need to be in place for the kind to exist at all, but they need not be directed towards the kind itself.

The second kind of social kind is mind-dependent in a stronger sense; here, certain specific attitudes towards the kind itself need to be in place for the kind to exist in the first place, but individual tokens of that kind might come into being without those attitudes being manifested towards them.

The third kind are social kinds whose very existence depends on specific attitudes towards the kind itself, and whose individual instances must also be deemed by at least some people to be members of the kind for them to be members of the kind.

Having established this three-fold classification of social kinds, I will go on to argue that it enables us to ascertain what would preclude some social kinds from being natural kinds. Rather than their very mind-dependence, I will propose a different reason as to why some social kinds are not natural kinds.

There are several accounts of natural kinds in the philosophical literature, but one common denominator among many of them is the idea that natural kinds are associated with causal properties. A natural kind is generally considered not to correspond to a single property but to a set or cluster of such properties, and these properties are thought to be causal properties.

When the properties associated with a natural kind are manifested or co-instantiated, they give rise causally to a host of other properties, or initiate one or more causal processes wherein these other properties are manifested.

To take an uncontroversial example, the chemical isotope lithium-7 is associated with the properties atomic number 3 and mass number 7. What makes lithium-7 a natural kind is not just the regular co-occurrence of these two properties in nature, but the fact that a host of other properties follow causally from those two properties, such as characteristic values for density, melting point, electrical conductivity, half-life, and so on. These other properties are causal consequences of one or both of the two properties associated with this chemical isotope. Hence, the categories corresponding to natural kinds feature in causal laws and generalizations. They are also the basis of a variety of inductive inferences and are projectible from one sample to another or from one instance to another.

Some philosophers may regard this account of natural kinds to be a minimalist one, since it does not stipulate that the causal properties associated with natural kinds be microstructural (as in the above example), or that they be both necessary and sufficient for membership in the kind, or that they be modally necessary, and so on. At least some of these additional conditions are required by essentialist accounts of natural kinds. But the essentialist conditions on natural kinds do not even seem to apply to biological kinds and can also be questioned on independent grounds. Since I cannot justify this claim within the scope of this article, I will proceed by considering this to be a necessary condition on natural kinds, which is shared among a variety of accounts. If social kinds cannot satisfy this minimal condition, then they would be disqualified from being natural kinds.

In principle, it would appear that this causal condition on natural kinds could well be satisfied by at least some social or human kinds. There is no reason to think that causal properties and relations do not exist in the social or human realm. I have already argued that the existence of individual instances of social kinds like war is at least partly dependent on their causal properties. This would seem to be true also of social kinds like money. For instance, it would be an exaggeration to say that there are no physical or causal constraints on the tokens of a social kind like money. Money cannot very well be made out of ice (at least not where temperatures often rise above 0° C), or a radioactive isotope with a very short half-life, or a rock the size of the moon. So the nature of these kinds is significantly constrained by causal factors rather than simply the attitudes of human beings. An argument along these lines has also recently been made by Guala (2010, 260), who writes with reference to the kind money: “What counts as money does not depend merely on the collective acceptance of some things as money, but on the causal properties of whatever entities perform money-like functions… . ”

This applies, even more clearly, to exemplars of the first kind of social kind, such as recession. What it is for a period in economic history to be a recession depends on economic transactions, the demand for commodities, the amount of trade and industrial activity, the level of unem ployment, and so on. These phenomena involve actions of human beings or processes in which human beings are engaged that involve the manifestation of causal properties.

The causal properties of humans in a social setting pertain to their abilities to perform certain functions as social beings, whether in coordination with others or in opposition to them.

These causal powers may be supervenient on physical powers but they are genuinely distinguishable from them, just as biological causal powers are distinguishable from physical ones.

With regards to the first two kinds of social kind, whose nature depends at least in part on their causal properties and not just on human mental states, there is nothing to prevent them from being natural kinds. But when it comes to the third kind of social kind, the existence of both the type and the token depends directly on human mental states, and the properties associated with them tend to be explicitly stated in a set of rules or conventions. Therefore, if such a kind is associated with a set of properties, that is not because there are causal connections between these properties or because they are linked together by laws or empirical generalizations. Rather, it is because a social institution or community has decided to associate these properties with the kind. Any relations between these properties are not the result of causal processes but the outcome of a conventional linkage between them.

The main impediment to some social kinds being natural kinds has to do with the fact that the properties associated with them are so associated because of social rule or convention. This implies that these kinds are invented rather than discovered. Their properties are explicitly written into them and can be as arbitrary as one pleases. If a legislative body were to decide to impose a condition on permanent residents of a certain jurisdiction that they be capable of swimming 100 meters underwater, then this would become a property of all permanent residents in that jurisdiction. However, even though this is a causal property of human beings, the connection between the property of being a permanent resident and being capable of swimming 100 meters underwater does not constitute a genuine causal rela tion. Since it has arisen as a result of legislative fiat, it would not reflect a causal connection between the properties involved. The category permanent resident cannot be considered a natural kind based on such conventional links. To put it differently, in this hypothetical scenario, no sociologist would be awarded a research grant to investigate the link between being a permanent resident and being a proficient underwater swimmer (though it may be interesting to ascertain why the legislators imposed such a condition).

It is important to see that it is not that the third kind of social kinds can not participate in causal processes; indeed, there would seem to be two principal ways in which they can do so.

① First, it may be that the associated properties and conditions of membership in the kind have been formalized based on causal patterns that existed before the rules and regulations were drawn up. Thus, the status of metic (permanent resident) in ancient Athens was regulated and formalized in the constitution of Cleisthenes in 508/7 BCE, but this status was already conferred informally prior to this legal development. Some of the social roles that metics had, such as participation in economic transactions and in military service and non-participation in the political process and in owning property, were likely already in place before they were formalized by the constitution of the late sixth century BCE. But surely, it might be objected, insofar as they had these properties, they were conferred on them by others. It is not as if they did not have the brute cau sal power to own property, but that it was not sold to them by others, per haps as a result of prejudice or an informal convention. True enough, but causal properties in the social world are frequently a relational matter, and this is also true of some causal properties outside the social realm. Take a property like biological fitness or adaptiveness: this is not generally a matter of pure causal power on the part of an organism, but of relational properties involving the organism and its environment. If the environment changes, an organism that was once fit or adapted will no longer be such. Therefore, there may be causal properties in the social realm that are later codified according to regulations or laws. The conventional links that are central to the third kind of social kind may be the result of codifying some preexisting causal links, which are then regulated as a result of formal rules. In this case, the codification of these causal links renders them conventional rather than causal, though remnants of the causal relations may persist.

② There is a second way in which the third kind of social kind can be implicated in causal as well as conventional relations. Once the conditions for membership in the kind have been fixed by convention or law, the properties associated with the kind may come to participate in new causal patterns that were not in existence before the creation of the conventional kind. For instance, we might discover that most permanent residents of a certain state are urban dwellers. This would be very different from discovering that most permanent residents do not have a criminal record (at least at the time that they become permanent residents) because that condition has been written directly into the category itself. In such cases, even though the kind originated as a conventional kind it may come to participate in causal processes in a particular social setting, thus potentially allowing it to become a natural kind.

For the most part, I have been treating social kinds as belonging exclusively to one or the other of these three kinds, but some social kinds may belong to more than one of these kinds in different contexts. There can be more or less conventional interpretations of some of these categories, and causal and conventional links may be interrelated in certain ways. Rather than consider some social kinds as belonging to one or the other category without qualification, we might distinguish a more and less con ventional version of some of these kinds. This may be the case with the kind permanent resident in ancient Athens, which may have undergone a transformation from belonging to the second category of social kinds to the third category, as the status of permanent residents was formalized in legislation. But it might be reasonable to consider it to straddle the two categories.

4. Objectivity and Mind-Dependence

The discussion in the previous section suggests that what would prevent some social kinds from being natural kinds is their being associated with a set of properties as a matter of conventional rather than causal links. But it might be protested that this ignores the fact that all three kinds of social kinds that I have identified are mind-dependent, and it is surely their mind dependence that makes them ontologically subjective, as Searle says. Moreover, their ontological subjectivity is an impediment to their being natural kinds, since natural kinds are supposed to be objective features of reality. I will argue that this approach to the ontological status of social kinds, and to realism more generally, is misguided.

It has become customary for philosophers to speak of a “mind-independent reality” or to use mind-independence as a criterion for realism about a set of entities. As Devitt (2005, 768) puts it:

The general doctrine of realism about the external world is committed not only to the existence of this world but also to its ‘mind-independence’: it is not made up of ‘ideas’ or ‘sense data’ and does not depend for its existence and nature on the cognitive activities and capacities of our minds.

The basic impulse behind this idea is not hard to ascertain. Insofar as we are realists, we want to exclude from our ontology fictional entities that we have merely conceived or conjectured and whose only claim to existence is based on their occurrence in our mental cogitations. The condition of mind independence would seem to capture the idea that real entities must not be figments of our imagination or posits of our other mental processes. But it is clear that there are many products of the human mind that have no less a claim on reality than anything else. Artifacts and artifactual kinds are largely human creations, but so are many chemical and biological kinds, for instance elements or compounds that are synthesized in the lab, such as roentgenium and polyethylene, or hybridized, artificially selected, and genetically engineered plants or animals, such as triticale, canola, dogs, and horses. [가능한 반론: causal dependance / constitutive dependance의 도입] Indeed, at least according to many philosophers, mental states themselves are real, and the criterion of mind-independence would automatically exclude them from being candidates for being real. Hence, it appears to be a mistake to ground realism in mind-dependence, since it would assimilate social and psychological kinds like horses and war to such fictional kinds as unicorns and wizardry.

Two moves might be made to save mind-independence as a criterion for realism.

① The first would make a distinction between causal and constitutive mind-dependence. Causal mind-dependence, it is sometimes said, is not inimical to realism about individuals or kinds, but constitutive mind-dependence is. Thus, Boyd (1989, 22) writes:

"The realist differs from the constructivist in that (like the traditional empiricist in this instance) she denies, while the constructivist affirms, that the adoption of theories, paradigms, conceptual frameworks, perspectives, etc. in some way constitutes, or contributes to the constitution of, the causal powers of, and the causal relations between, the objects scientists study in the context of those theories, frameworks, etc. The realist does not deny (indeed she must affirm) that the adoption of theories, conceptual frame works, languages, etc. is itself a causal phenomenon and thus contributes causally to the establishment of, for example, those causal factors which are explanatory in the history of science and of ideas. What she denies is that there is some further sort of contribution (logical, conceptual, socially constructive, or the like) which the adoption of theories, etc. makes to the establishment of causal powers and relations."

However, the “further sort of contribution” and the relevant notion of constitution or constitutive mind-dependence do not appear to have been clearly articulated by proponents of this criterion. Moreover, there are principled grounds for doubting that the distinction between constitution and causation could be used to draw the line in the right place. We may have a clear sense that unicorns are constituted by human minds whereas horses are merely caused by them. But if unicorns are constituted by human minds, so are kinds of psychological states themselves, such as beliefs, desires, pains, and depressions.

Hence, any attempt to demarcate real entities using a criterion of constitutive mind-dependence would rule out mental or psychological states and regard their existence to be on a par with fictional kinds. [???]

Whatever we say about the existence of beliefs, desires, pains, and depressions, we should surely not relegate them to the same status as unicorns and wizardry.

② A second attempt to modify the criterion of mind-independence may advert to modal considerations. While those kinds that are necessarily mind-dependent cannot be real, those that are merely contingently mind-dependent can be. The idea here might be that while polyethylene and horses could have come into existence in the absence of minds, unicorns and wizardry could not have. But this modification would place not just psychological kinds, but also social kinds, in the same category as unicorns and wizardry, since the existence of minds is surely necessary for both psychological and social kinds to exist.

On reflection, it seems problematic to ground realism in mind-dependence, since there is nothing inherently unreal about all entities that depend on the mind in some way. Mind, like life, is a phenomenon in the natural world that pertains to certain complex systems and there is no reason to regard any constituent of the universe that is dependent on the mind as being ontologically tainted in some way. Mind-dependence is a red herring [훈제청어] when it comes to ontological objectivity. There are various phenomena that depend on the human mind (both causally and constitutively) yet are not non-real, at least not in the same sense as fictional entities.

Still, isn’t there a sense in which all social kinds are ontologically subjective, as Searle claims? Doesn’t the fact that they would not have existed without the existence of human minds render them ontologically different from other kinds? Some perspective on these questions may be gained by reflecting further on the analogy between mind and life.

Consider biological kinds like tiger, larva, and metabolism. It is safe to say that these biological kinds are life dependent, in the sense that they would not have existed without life. But that does not seem to impugn their ontological objectivity, and nor should the mind-dependence of social (and psychological) kinds. Moreover, it is questionable whether one can effect a compromise, as Searle attempts to do, between ontological subjectivity and epistemic objectivity. Searle maintains that facts about social kinds can be epistemically objective, even though the kinds themselves are ontologically subjective. But it is not clear that he can have it both ways. Fictional characters like Sherlock Holmes are plausibly held to be ontologically subjective and any facts or judgments about them will be correspondingly epistemically subjective, such as the ‘fact’ that Holmes lived at 221B Baker Street. We may want to make a distinction between ‘facts’ about Sherlock Holmes that are consistent with the writings of Arthur Conan Doyle and those that are not (e.g. that he lived at 221A Baker Street, or had a dog named ‘Rover’), but the former are not objective facts about the world. If individuals or kinds are truly ontologically subjective, it is not clear that one can maintain that facts about them are epistemically objective. Hence, it is far from obvious that one can assert both that social kinds are ontologically subjective and that facts about them are epistemically objective.

Though all social kinds can be said to be mind-dependent, there are genuine grounds for distinguishing the first two kinds of social kinds from the third kind. The main difference is that the former are characterized by causal links among their associated properties, whereas the properties associated with the latter are linked by convention. This constitutes an important difference between different kinds of social kind and it is arguably the reason that some social kinds cannot be deemed to be natural kinds. What differentiates the third kind of social kind from the other two is not mind-dependence but dependence on convention or regulation.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, I have distinguished three kinds of social kinds, all of which are mind-dependent, though in significantly different ways.

① The first kind are dependent on human propositional attitudes though not about the kind itself.

② The second kind are dependent on attitudes about the kind itself, though the existence of individual members of the kind may not be so dependent.

③ The third kind of social kind depend for their existence on propositional attitudes about the kind itself, and individual members of the kind depend for their existence on someone having the relevant attitudes towards them.

This third kind of social kind coincides with the most conventional of social kinds. The reason that instances of the third kind of social kind may not be natural kinds is not that they are mind-dependent but that the properties associated with them are conventionally rather than causally linked.

There is a broader point to this discussion, which goes beyond the question of the classification of social kinds, or even the question of whether some social kinds could be natural kinds. A consideration of the ontological status of social kinds suggests that mind-dependence is simply not relevant to the question of realism about kinds. Mind-dependence is a red herring in this context because it cannot distinguish social kinds from mere imaginary or fictional kinds. What seems to differentiate social kinds that are at least prima facie candidates for being natural kinds from those that are not is that the former are associated with properties that are causally related whereas the latter are associated with properties that are conventionally related. This conventional aspect, not mind-dependence, is what disqualifies some social kinds from being natural kinds.

Q1) Does the existence of the kind depend upon our having certain attitudes toward it?

Q2) Does the existence of instance of the kind depend upon our having certain attitudes toward it?

Sk1: Neg Q1; Neg Q2 do not depend on one attitudes toward kind or their instances ex) Racism, Recession + Other social -ismus, disability, anarchy

Sk2: Pos Q1; Neg Q2 do not depend on one attitudes toward instances, but yes towards the kinds ex) Money, War

Sk3 Pos Q1; Pos Q2 Either exitence depends on specific attitudes towards the type and its instances ex) Permanent resident, Prime minister, Cocktail party

'Metaphysics and Epistemology > Social Ontology' 카테고리의 다른 글

| K. Koslicki (2018) Artifacts, in: Form, Matter, Substance Ch. 8 (0) | 2024.09.17 |

|---|---|

| Bettcher (2014) Trapped in the Wrong Theory: Rethinking Trans Oppression and Resistance (0) | 2024.09.14 |

| Searle (1995) The Construction of Social Reality Ch. 2 (0) | 2024.09.06 |

| Searle (1995) The Construction of Social Reality Ch. 1 (0) | 2024.09.02 |

| Mason & Ritchie (2020) Social Ontology (0) | 2024.08.28 |